Commentary by Donald Knebel

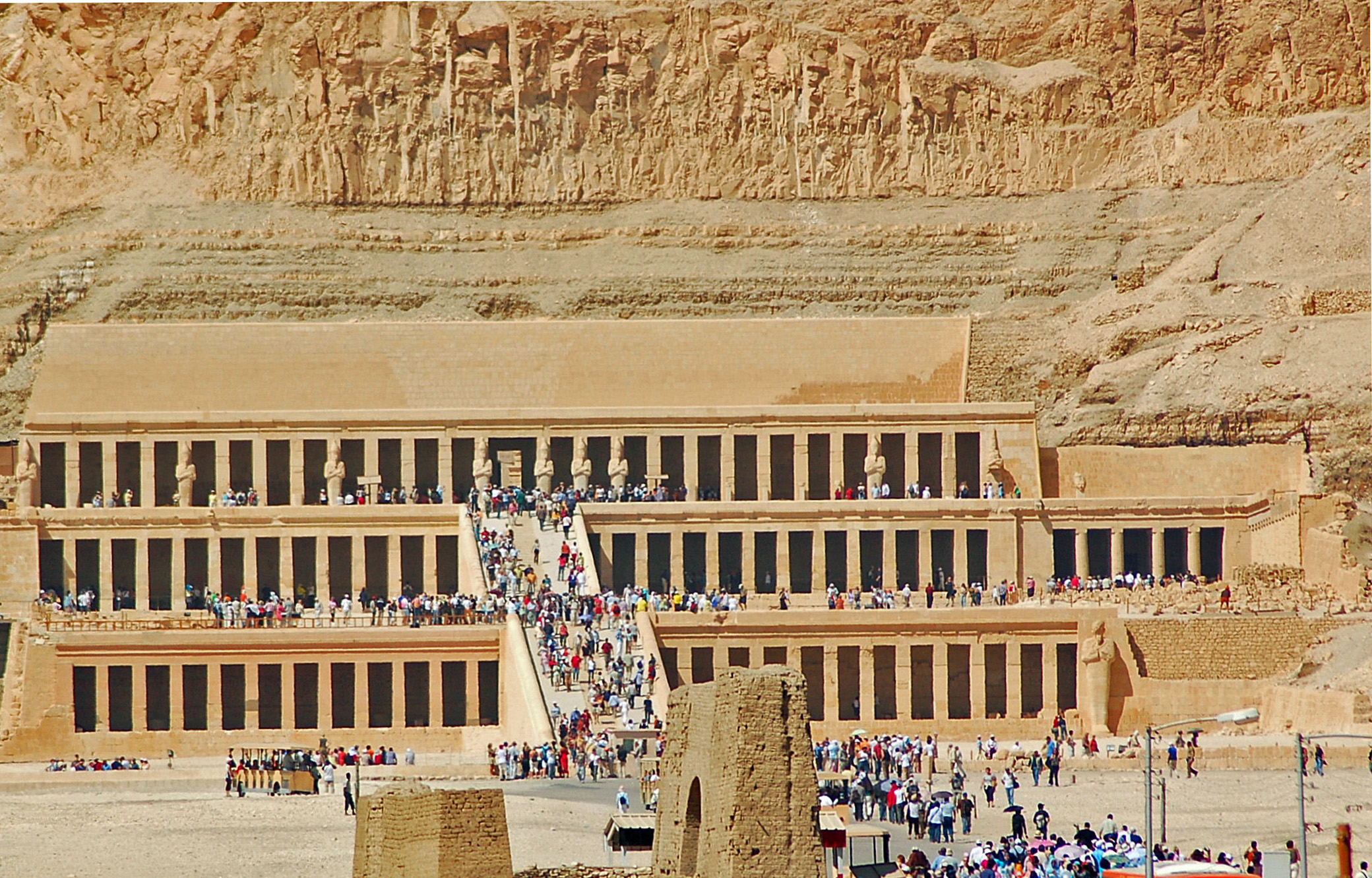

Near the entrance to Egypt’s Valley of Kings, beneath a pyramid-shaped mountain, is a magnificent 3,500 year-old temple that even today is considered a model for adapting a building to its surroundings. Hatshepsut, the powerful female pharaoh honored by this mortuary temple, was unknown until the twentieth century. Her successors had tried to erase not only her memory but her very existence.

Hatshepsut was born in 1508 B.C., the daughter of Thutmose I, the first pharaoh entombed in the Valley of the Kings. After a brief stint as regent for a young male pharaoh, Hatshepsut declared herself pharaoh in 1479 B.C. During her reign, she dressed as a man, even wearing a false beard strapped around her head. One of the most successful rulers of her era, she greatly expanded Egyptian trade and engaged in a massive building program unmatched for centuries. One of the many buildings she constructed was her mortuary temple at a complex now called Deir el-Bahri, dedicated at her death in 1458 B.C.

Like other pharaohs, Hatshepsut made sure that the walls of her colonnaded mortuary temple contained numerous images of herself and hieroglyphic representations of her name. Egyptians believed that their ka, the essence of their being, could live on after their deaths in a physical representation of the deceased, such as an image or an inscribed name.

Pharaohs ruling after Hatshepsut tried to eliminate any place for her ka to reside. They destroyed her statutes, obliterated her images on temple walls and erased her name from everything they could find, including lists of pharaohs. Scholars believe these pharaohs saw depriving Hatshepsut’s ka of a place to live as a way to restore Ma’at, the natural order of the universe they thought had been upset by their female predecessor.

Twentieth century archaeologists reconstructed Hatshepsut’s lost reign from images overlooked for destruction. Her mummy, found without markings, was identified in 2007 when a tooth known to be hers matched the mummy’s empty socket. Hatshepsut’s mummy now lies alongside those of other great pharaohs, all men, in the Cairo Museum. Many would say the true natural order has finally been restored.