A Broadway musical set against the backdrop of a community of rural Jews living in early 20th Century tsarist Russia, forced to leave the only home they’ve ever known. Think that concept was an easy sell to the powers-that-be on 42nd Street? Think again. When Sheldon Harnick, Jerry Bock, and Joseph Stein brought their idea to Broadway, the whole concept – a musical based on the short stories of Yiddish author Sholem Aleichem – was considered “too Jewish” to appeal to mainstream theatre goers.

Indeed, initial reviews of “Fiddler” were not good. The show, produced by Broadway heavyweight Harold Prince and directed and choreographed by the great Jerome Robbins, made its premier in Detroit – then migrated to Broadway. Highbrow critic reviews notwithstanding, audiences ate up “Fiddler.” Ticket lines snaked around several blocks of Manhattan real estate. New York had never seen anything like this before. What was it about “Fiddler on the Roof” that was captivating America?

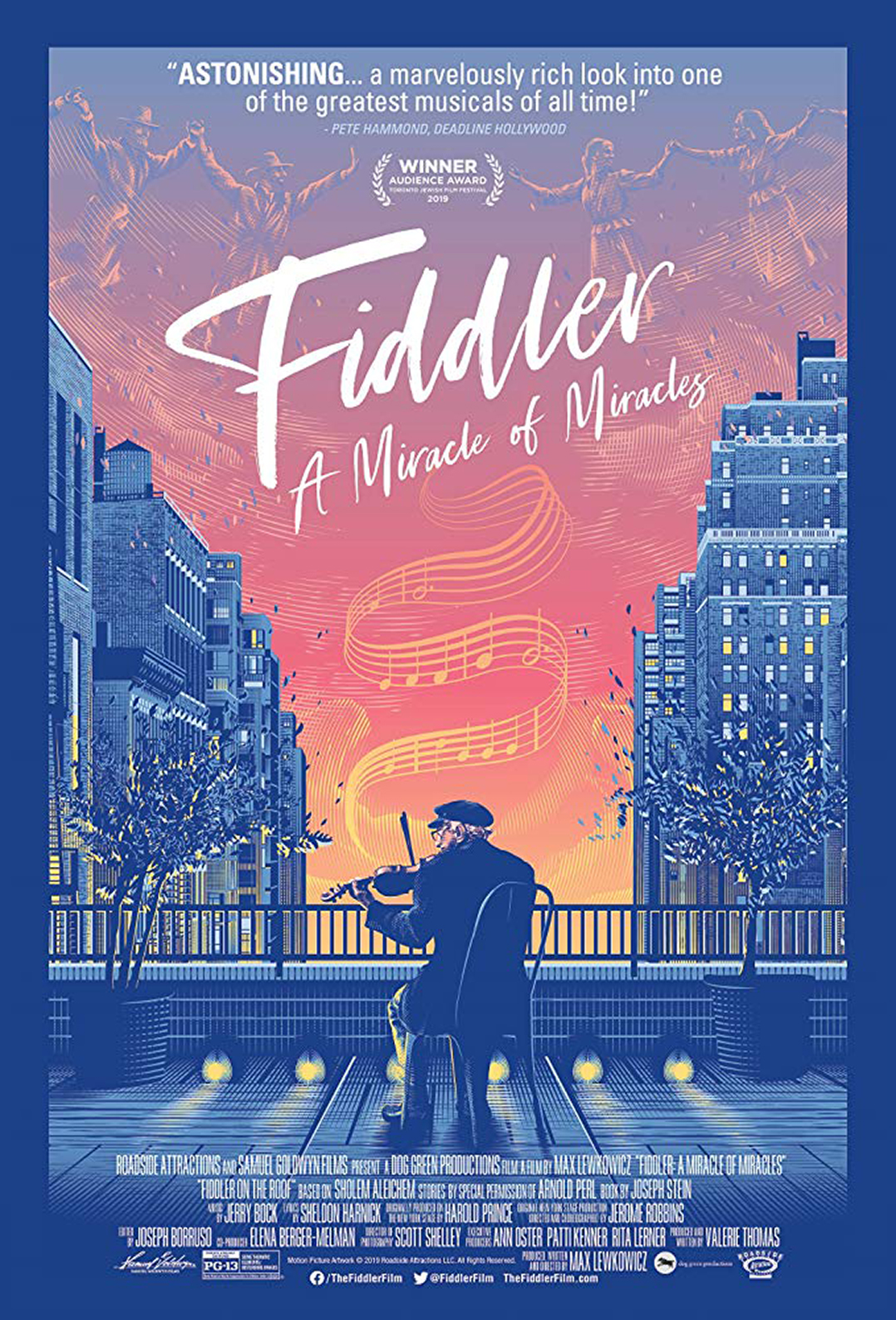

Director Max Lewkowicz tries to capture the essence of this Broadway mainstay in his new documentary “Fiddler: A Miracle of Miracles” – in which he highlights the obstacles encountered in bringing this musical to the stage, but also explores the captivating legacy of this giant of the stage and screen. Told with no narration, “Miracle of Miracles” features the talking heads of many of those associated with “Fiddler” over the years – including Harnick and Bock, as well as character actor Austin Pendleton, who made his debut in the original Broadway production, and is still active in film work today.

There are just a few musicals which rise to a level above and beyond all others. Musicals in which almost every song is a classic. “West Side Story,” “The Sound of Music,” “My Fair Lady.” And yes, “Fiddler on the Roof.” Think of the lasting heritage of the songs – “Tradition,” “Matchmaker,” “If I Were a Rich Man,” “Sabbath Prayer,” “To Life,” “Miracle of Miracles,” and “Sunrise, Sunset.” And that’s all before intermission!

As “Miracle of Miracles” points out, “Fiddler” always draws a crowd. Whether a Broadway revival, a local theatre production, or a school play, if filling every seat in the house is the goal, bring out “Fiddler.” For such an odd topic for a musical, and with such seemingly limited appeal, “Fiddler on the Roof” has been entertaining audiences for over a half-century.

But alas, the music is just one aspect of its success. The emphasis on family and tradition is obviously another. But Lewkowicz does an admirable job of placing “Fiddler’s” 1964 Broadway opening within historical context. America’s involvement in Viet Nam was in its infancy, and social mores were just beginning to change. In “Fiddler,” one of protagonist Tevye’s daughters elects to marry outside the tradition of arranged marriages. While such a decision affects almost no one in today’s culture (nor in that of 1964, for that matter), it symbolized the societal challenges to religion, race relations, sexuality, and gender roles that were just beginning to take hold in America.

“Fiddler” affirmed the usefulness of the traditions of family and society for older audience members, while gently asserting the younger generation’s need to challenge some of these customs. Thus, its appeal was so wide that every audience member took away something different – and something personal – from experiencing “Fiddler.” Lewkowicz also ties the vagabond nature of the show’s characters to our present refugee crisis along our Mexican border. Without making a blatant political statement, “Miracle of Miracles” exemplifies the universal nature of the themes of this greatest of American musicals.

Some audiences may be less interested in the ins and outs of the theatre world, but I was most fascinated by the discussion of Robbins’ demanding (and occasionally abusive) leadership style, and the mutual disdain between Robbins and star Zero Mostel. Mostel was chosen because, as one interview subject points out in “Miracle of Miracles,” Tevye was larger than life; he had to be played by someone who could carry the entire show on his broad shoulders. Enter Mostel. But Mostel always harbored resentment against Robbins for testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee during the Communist witch hunts of the 1950’s – and for masking his Jewish heritage. Again, Lewkowicz does an excellent job of placing “Fiddler” within historical context.

I was also mesmerized with several facts about the 1971 Hollywood motion picture version, directed by Norman Jewison. First, I had no idea Jewison was Christian – a fact kept hidden from most of the cast until after filming had wrapped. How could a Christian director possibly understand the trials of “Fiddler’s” cast of characters? I think the result speaks for itself, but it does beg the question why a Jewish director wasn’t chosen in the first place.

I also assumed Israeli actor-comedian Topol was chosen to play Tevye simply because Mostel was busy with other projects during the filming schedule. Come to find out, Jewison chose Topol because he thought he was a better fit for the film version. Would Mostel have made an impression in a film adaptation of “Fiddler?” Of course! But it’s hard to imagine anyone other than Topol playing Tevye on the big screen, having seen the magnificent outcome. Not to mention, Topol is an inherently superior singer than Mostel was.

Clocking in at just over 90 minutes, I could have watched another hour of discussion of both the inner workings of “Fiddler on the Roof” and its social impact. But even for those with no interest in the theatre, “Miracle of Miracles” is almost essential viewing because Lewkowicz devotes as much time to its impact as to the personality clashes and casting decisions. This is an important documentary about an important cultural phenomenon.

One final footnote: Hardly any footage exists of the original Broadway production. When we see Mostel and certain cast members act out scenes from the show, we are watching their performances on television programs, such as “The Ed Sullivan Show.” Instead, “Fiddler: A Miracle of Miracles” shows us footage from recent Broadway revivals, intermixed with footage of small-town theatre productions, and even school musicals.

The universality of the show is highlighted by scenes of performances in Japan and Thailand – complete with subtitles – as we watch actors bring this small, personal story of Russian Jewish hobos to cultures halfway around the world. The experiences of the characters in “Fiddler” are so far removed from those of Asian audiences they may as well live on the moon. But its themes are so universal, anyone can relate to the story and the characters. And oh, that music. Is it any wonder “Fiddler” still draws a crowd 55 years after its premiere?