British filmmaker Joe Wright’s latest feature “Darkest Hour” opens with a sullen and possibly inebriated Winston Churchill dictating a letter to his personal secretary Elizabeth Nel. Disgusted with her inability to keep up with his ramblings, he bullies her out of his office and demands a replacement. Consoled by his loving wife Clementine, Churchill decides to give her another chance.

The fact that Elizabeth’s (or Nel’s, as Churchill liked to call her) story is even included in “Darkest Hour” is testament to the most clever cinematic technique Wright uses in his biographical portrait of the early portion of Churchill’s reign as British Prime Minister. On the one hand, it’s delightful to see the innerworkings of the halls of the executive (and legislative) branches of government though the eyes of one not privileged to grow up in that world. Yet it’s refreshing this narrative tool is only utilized within the structure of the screenplay. Nel’s inclusion is merely for point-of-view reference and not as a narrative reference. In other words, we’re not burdened with a constant barrage of, “As Winston approached the lectern, no one was quite sure what was to come out of his mouth.” No, Wright and screenwriter Anthony McCarten (“The Theory of Everything”) are wise enough to know we can mentally write our own voice-over narration without their having to provide one for us.

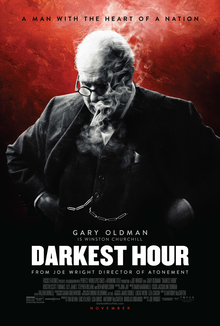

That’s the best structural achievement of “Darkest Hour.” The best acting achievement is the crowing jewel in the long (and unfortunately often overlooked) acting career of the great British actor Gary Oldman – a man who’s already played Lee Harvey Oswald, Count Dracula, and Ludwig van Beethoven. But this is his best. This is the performance that will win Oldman his Oscar. And he’ll deserve it. In fact, Oldman’s work is actually superior to the film itself. While “Darkest Hour” has a tendency to drag in spots – a common feature of these behind-closed-doors government policy accounts, like Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” – Oldman’s captivating Churchill keeps drawing us back into the proceedings.

Oldman doesn’t merely impersonate Churchill; he embodies the man. When you watch “Darkest Hour,” you’ll see Winston Churchill; you won’t see Gary Oldman. By contrast, remember “Hoffa?” You didn’t see Jimmy Hoffa; you saw Jack Nicholson playing Jimmy Hoffa. That’s not the case here. Oldman’s Churchill is alive and brimming with confidence. And it’s spot on – even down to the occasional partially-drunken ramblings followed by a burst of oratorical brilliance. I could have watched Oldman portray Churchill in a one-man stage show and been equally as mesmerized as I was watching him in “Darkest Hour.” He’s that good.

The rest of the cast is strong. Kristen Scott Thomas plays Churchill’s long-suffering but supremely devoted and supportive wife; Ben Mendelsohn is King George VI; Ronald Pickup is the recently ousted prime minister Neville Chamberlain; and Lily James (of “Downton Abbey”) shines in the role of Nel.

The screenplay follows Churchill’s very early days as prime minister, in which he was immediately tasked with forming a new government (in which he included as many political enemies as he did the likeminded) and bringing stranded British soldiers home from the French coastal city Dunkirk. Ring any bells? Yes, that Dunkirk. And yes, “Dunkirk” and “Darkest Hour” work together as companion pieces, and it doesn’t matter which you watch first. You’ll get the soldier-on-the-ground point-of-view from Christopher Nolan’s “Dunkirk,” and you’ll get the behind-the-scenes maneuvering from “Darkest Hour.” In “Darkest Hour,” we see the puppeteers pulling the strings of the rescue mission depicted in “Dunkirk.” It’s almost as though Nolan and Wright planned these films to be released together. (They didn’t, but it worked out that way – like “12 Years a Slave” and “Lincoln.”)

Again, “Darkest Hour” does drag just a bit in the middle, but there are some excellent individual scenes, including a phone call from Churchill to U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt asking for military assistance. We can feel the sense of despair overcoming Churchill as Roosevelt cracks jokes. But the speeches. Oh my, the speeches. His political rivals described Churchill as an empty glass, empowered only by his oratorical brilliance. But, as “Darkest Hour” depicts, it was that eloquent rhetorical skill that rallied all of Great Britain to the task of defeating the Nazis.

Nel’s 1958 memoir “Mr. Churchill’s Secretary” best sums up the man in these words: “Sometimes (while dictating a letter) his voice would become thick with emotion, and a tear would run down his cheek. As inspiration came to him, he would gesture with his hands, just as one knew he would be doing when he delivered his speech, and the sentences would roll out with such emotion that one died with the soldiers, toiled with the workers, hated the enemy, and strained for victory.” Thanks to Wright and Oldman, we can now experience this too.